Perspectives is an ongoing series by the Cari-Bois Environmental News Network which aims to give Caribbean scientists, explorers and nature enthusiasts the platform to share their experiences. This latest piece was written by Khadija Stewart, Sustainable Ocean Alliance (SOA) Caribbean Regional Representative. Khadija has been attending meetings by the International Seabed Authority in Jamaica on the issue of deep-sea mining.

Even though the deep sea accounts for more than half of the earth’s surface, it remains largely unexplored with scientists knowing more about the moon.

The National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) defines any part of the ocean below 200 metres (656 feet) as the deep sea and at this point, sunlight begins to fade.

Despite the absence of light, the deep sea contains an array of species which have evolved to produce their own light and survive the extreme conditions.

In the deep sea, researchers have also found various geological features like abyssal plains (at depths of 3,500–6,500 m), seamounts, underwater volcanoes, hydrothermal vents and deep trenches like the Mariana Trench.

An introduction to deep-sea mining

With efforts underway to start deep-sea mining activities, environmental bodies and civil society organisations – including the IUCN, the Sustainable Ocean Alliance (SOA) and the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition – have expressed concerns about the looming industry’s potential effects on marine ecosystems and species.

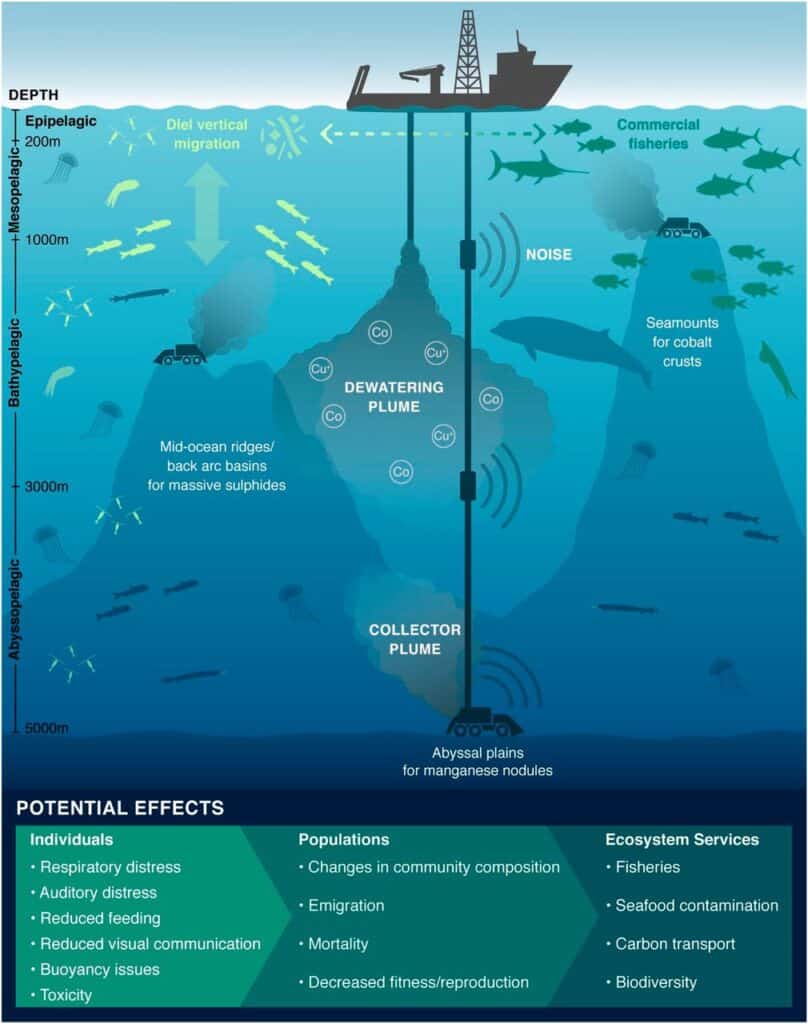

Deep-sea mining is the process of extracting mineral deposits like polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulfides, and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts from the deep seabed at ocean depths greater than 200m.

These metals are used to manufacture batteries, smartphones, laptops, electric cars, photovoltaic systems and other types of power storage.

To extract some of these minerals, remote-controlled cutting and drilling tools will be required. But to extract others, a collection vehicle will be required.

Once collected, these materials will be piped to a collection vessel on the water’s surface.

From there, the minerals are processed and transported to land while the remaining sediments are released back into the water which some researchers predict will create an underwater “dust storm” with the potential to disturb deep sea life.

Is deep-sea mining necessary?

There are schools of thought which suggest the minerals sourced from deep-sea mining are needed to manufacture green technology as the availability of these minerals sourced land mining have dwindled.

Estimates have valued the looming deep-sea mining industry at USD$2-20 billion.

But it is fair to question if deep-sea mining will only contribute to the myriad of threats facing the ocean and affect the wider ocean economy.

Overtime, environmental issues like overfishing, climate change and pollution have stressed the health and well-being of oceans.

Environmental circles have raised concerns that deep-sea mining will only add to these existing pressures.

Are guardrails in place to properly manage deep-sea mining?

Overtime, extractive industries like fracking have shown that once a technology becomes commercially viable – and has the backing of both powerful industrial lobbies and national governments – it can be challenging to then create and enforce guardrails to sustainably manage their activities.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is currently hosting negotiations at its base in Kingston, Jamaica, to develop the rules and regulations that would govern the deep-sea mining industry.

The ISA is an autonomous organisation established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to organize, regulate, and control seabed mining.

As such, the body is tasked with the responsibility of managing the extraction of mineral resources on the seafloor in areas beyond national jurisdictions (ABNJ).

The ISA is mandated by Article 145 and 162 of the UNCLOS to prevent ‘serious harm’ and ensure the ‘effective protection of the marine environment’ from harmful effects, which may occur from seabed-mining activities.

If the current regulations by the ISA are approved and adopted, it will give the green light to deep-sea mining as soon as this year.

However, environmental bodies and groups are calling for more scientific research, and environmental impact assessments, to be conducted on the looming industry.

Advocacy efforts for more research on deep-sea mining

In 2021, the island nation of Nauru triggered a treaty provision known as the “two-year rule” which calls on the ISA to finalise and adopt regulations for deep seabed mining within two years (July 9, 2023).

While there are pro deep-sea mining countries like Nauru, there has also been a groundswell in the number of countries calling for a more measured approach.

In the past several months, 14 countries including the Dominican Republic have formally called for a precautionary pause or moratorium on deep-sea mining.

These countries join over 700 marine science, and policy experts, calling for the same and France which is calling for a total ban.

More than 100 non-governmental organisations like the Sustainable Ocean Alliance (SOA) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF), have also come together under the umbrella of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition in support of this movement.

Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica sit on the ISA council but have yet to join the growing call for a precautionary pause.

The most recent council meeting held from March 16 – 31, 2023, focused on negotiating the exploitation regulations and discussing the outcome of the two-year rule which was triggered by Nauru.

For some, the meeting was disappointing because the Council did not make as much progress on the issue as desired.

As negotiations continue, the world continues to be in a unique position to better understand the risks of deep-sea mining before it starts.

Sustainable Ocean Alliance (SOA) Caribbean’s position on deep-sea mining

“We are already in a triple planetary crisis as we deal with the impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution, we must err on the side of caution and truly assess greenlighting another extractive industry that can potentially have perilous consequences to ocean health.”

Sweelan Renaud, Social Media and Communications Manager, SOA Caribbean.

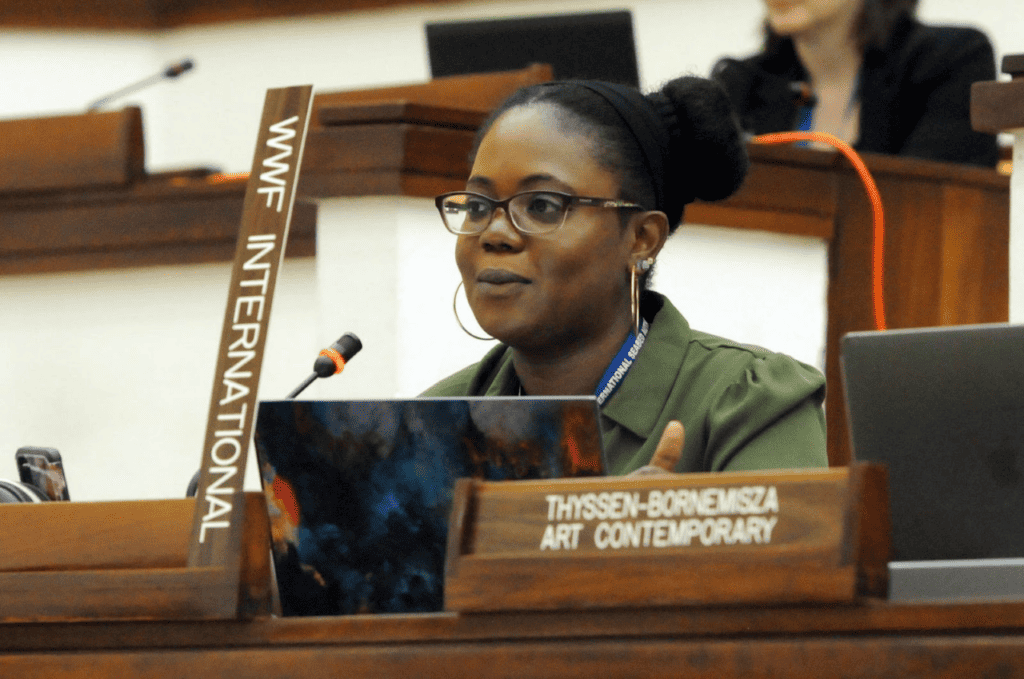

As the SOA’s Caribbean Regional Representative, I (Khadija Stewart) have been attending the ISA’s meetings in Jamaica to amplify youth voices and call for a stop to deep-sea mining.

As the only Caribbean youth representative present at the ISA, I have communicated the need for a precautionary pause and reminded the meetings delegated that the region’s youth are watching their decisions.

At the meetings, I have repeated the importance of taking preventative actions to ensure that no mining applications are approved this year, next year, or at any time, until there is enough science and assurance that the marine environment will be protected.

As July looms, and so do a decision on the future of deep-sea mining, it is imperative that more Caribbean leaders attend the ISA meetings and join the call for a moratorium.

“The ocean is worth more than just the value of its finite resources. The long-term benefits of a healthy ocean far outweigh any short-term incentives offered by deep seabed mining. Opening up this new frontier for extraction would destabilize delicate ocean ecosystems and fatally undermine the foundations of a circular economy”

Sustainable Ocean Alliance (SOA) Caribbean