Vincent Van Gogh’s love for nature was no secret and the olive groves in Saint-Remy, France, were one his favourite places to paint.

In a letter to his brother Theo, Van Gogh once wrote, “The murmur of an olive grove has something very intimate, immensely old about it….it’s too beautiful for me to dare paint it.”

What Van Gogh captures in his words is the reverence of nature which is often quite difficult to ignore when you are working in natural settings.

As a marine biologist, working in the sea allows one the good fortune of seeing many marine species living life in their natural habitat.

Regardless of size, every marine animal and plant holds an intrinsic value that is inescapable.

If you reflect on Van Gogh’s work in the olive groves, one can notice the value of organisms in nature was not lost on Van Gogh.

His paintings from the olive groves were sometimes accompanied by the sound of the chirping crickets as the insects reminded him of home in the Netherlands.

He once wrote, “Their (the crickets) song in times of great heat holds the same charm for me as the cricket in the peasant’s hearth at home.”

The charming effect of marine ecosystems

As a marine biologist, the charm of watching manta rays flap in their effortless majesty – while having early morning breakfast – is unmatched.

Watching sea turtles cautiously poke their heads above the water then dart away at remarkable speed, if I get too close for comfort, only to then poke their heads suspiciously above the water again as they track my every motion brings me indescribable joy.

While it is easy to focus on these charismatic species, biodiversity encompasses a much wider range of organisms that may not be commonly known.

Without some of these “lesser known” species, the stability of ecosystems may be affected and the more popular animals may cease to exist.

Allow me to highlight a few of the lesser known benthic organisms that might be of interest to the curious mind.

Much like Van Gogh and his crickets, benthic organisms hold a certain charm (though maybe not as much for the peasant’s hearth at home).

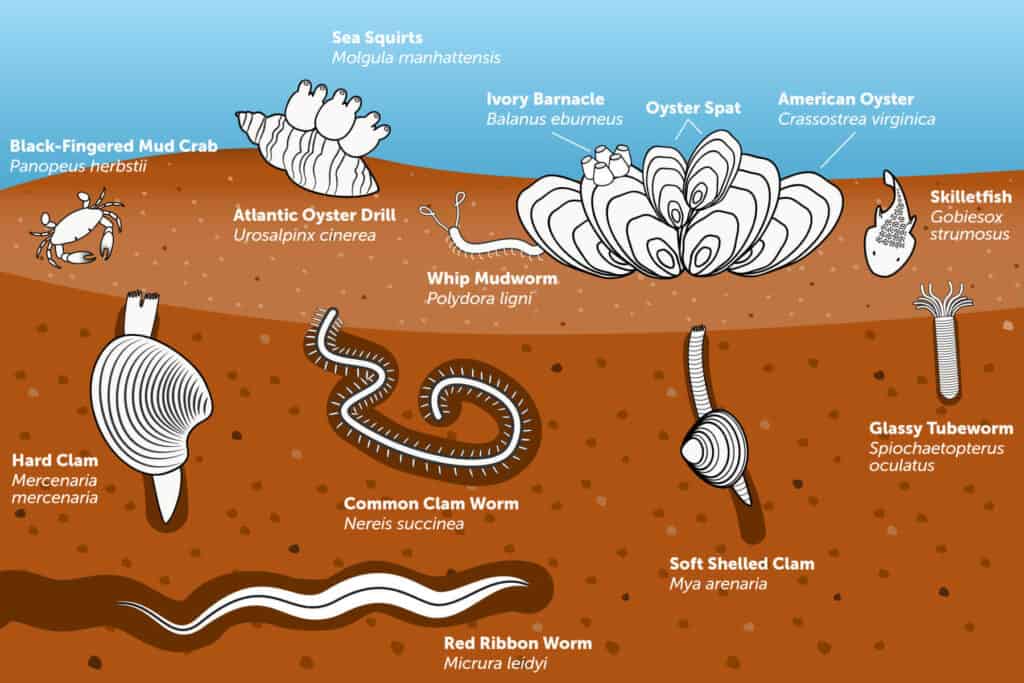

Benthic organisms consist of worms, crabs, bivalves, flowering plants, crustaceans and even fish.

These species burrow their way into the sand where they make their homes, hunt for food and provide essential services for the upkeep of marine ecosystems.

Types of benthic organisms and their importance

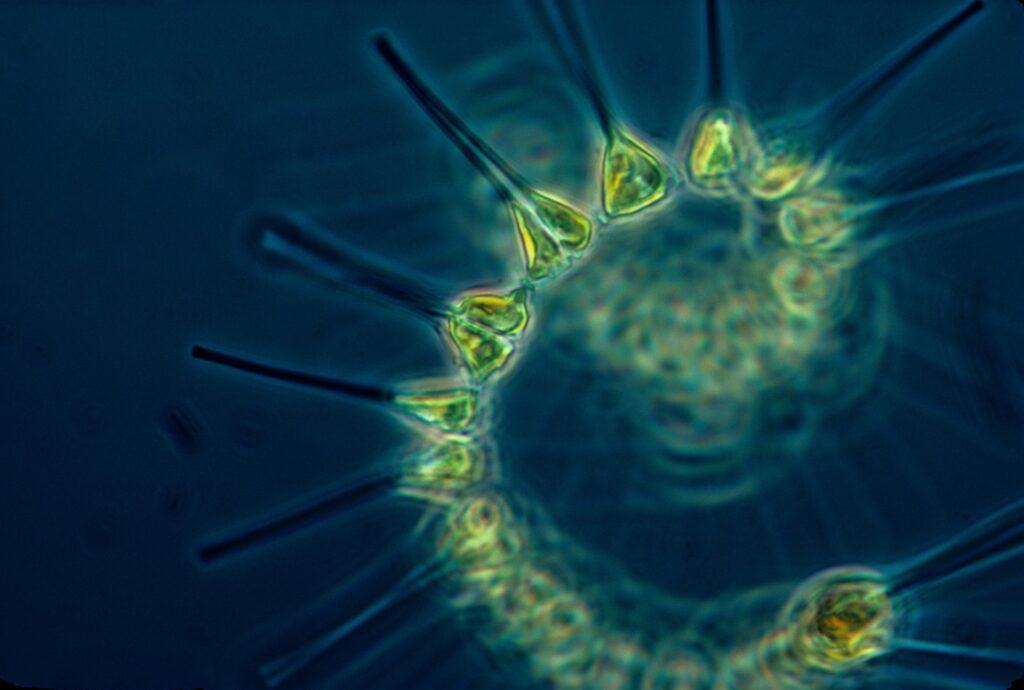

Some of the most charismatic benthic organisms are the polychaete worms.

Mention the word polychaete to any benthic ecologist and you’re sure to garner a smile. Polychaetes are varied, ubiquitous, and informative.

There are roughly 8,000 known species of polychaetes scattered all over the world. They are distinguished by their segmented bodies and consist of creatures with some fearsome names such as bloodworms, lugworms, rag worms and the not so cuddly seamice.

Some of them feed on aquatic plants, some are carnivorous, while others are omnivorous.

Not only are they nature’s carnival costumes, usually adorned with bright colours and feather-like appendages, but they are also serious story tellers.

Their most useful feature is their ability to serve as environmental indicators.

The presence or absence of some species can provide insight into whether any given area is clean, polluted or somewhere in between.

Sharing the seabed with polychaetes are the amphipod crustaceans. With more than 9,000 species discovered so far, amphipods exist not only in the marine environment but also in freshwater bodies and terrestrially.

Amphipods are not normally visible to the naked eye with the majority of them being less than 10 mm (0.4 in) long. However, some larger species can grow up to 28 cm (11in).

Amphipods are quite the deep sea divers and have been found at depths of 5,300 metres (17,400 ft) in the Pacific Ocean.

Amphipods are far more fussy than their polychaete counterparts and do not like a dirty house. For this reason you will seldom find them in areas where there is less than optimal water quality. A thriving amphipod population is normally a good sign that the aquatic environment is in a good state.

If you have ever walked along the beach looking for seashells then you are familiar with bivalves.

There are over 10,000 species of bivalves described throughout the world ranging from the deepest depths of the ocean to the shallowest streams of water.

Bivalves are most easily recognised by their two shells, although by the time you may have come across them on the beach, chances are their other half has probably gone missing.

They can be either epifaunal (reside on the surface of the sea floor) or infaunal (burrow into the ocean’s seafloor).

Historically bivalves have a close relationship to humans as they are a source of food, used for fashion and decorations.

Oysters, the reputed aphrodisiac and delicacy are probably the most famous example of bivalves.

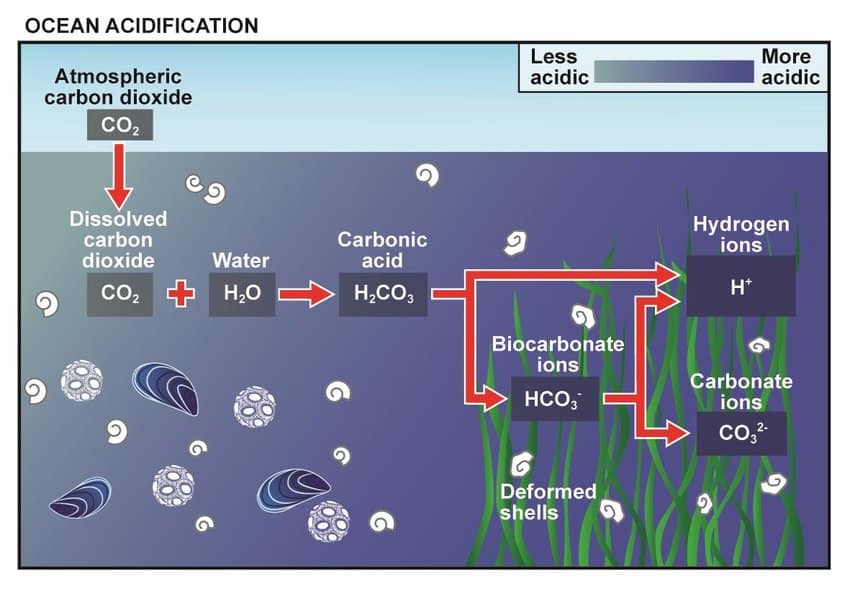

Unfortunately, not all is well in the bivalve world as ocean acidification threatens the well-being of these organisms.

Ocean acidification can simply be described as a decrease in the pH of the world’s oceans causing seawater to become more acidic.

Ocean acidification has led to the shells of bivalves becoming less structurally sound, smaller in size and more difficult for juveniles to even form shells.

This can have potentially detrimental effects not only for humans who rely on them commercially but to the ocean’s food web.

There is still much of the natural world that remains undiscovered. In April 1888, Vincent sent an order for canvas and paint to his brother Theo in Paris.

The request said, “For Christ’s sake get the paint to me without delay. The season of orchards in blossom is so short, and you know these subjects are among the ones that cheer everyone up.”

The urgency reflected by Van Gogh in procuring paint to capture seasonal blossoms should be reflected in the urgency which is needed to protect our many diverse, and maybe lesser known creatures, as they all play an important role in the world.

The greatest tragedy would be losing the beauty and wonder before we even discover them as all of these organisms are the very brush strokes painted on nature’s worldwide canvas.

What will artists of the future paint when there are increasingly less brush strokes to be added to nature’s masterpiece?