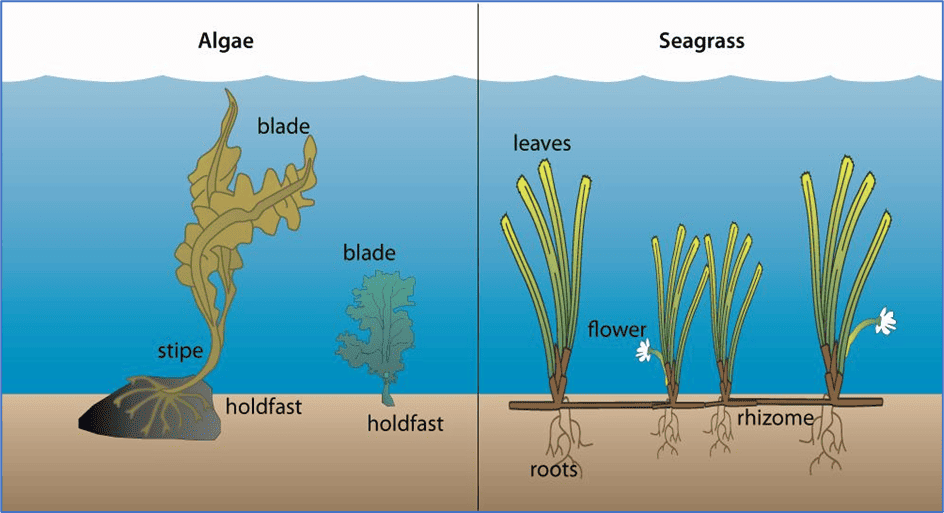

Ask someone with a good sense of humour what do they know about seagrasses and their response may be – the grass that sea cows eat? Yes, sea cows (manatees) do enjoy munching on seagrasses, but there is so much more to these underwater plants than this. Seagrasses are aquatic plants which are completely adapted to life under water. They are different from seaweeds, such as the widely known Sargassum, because seaweeds produce spores and are a type of Macroalgae, whereas seagrasses are spermatophytes and produce flowers.

Photo by: Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu), University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science

Evolution and Diversity

Seagrasses are thought to originate from the Indo-West Pacific Region (specifically in the Tethys Sea), all derived from a single lineage of flowering plants called Alismatales. Today, they can be divided into two groups – temperate and tropical seagrasses.

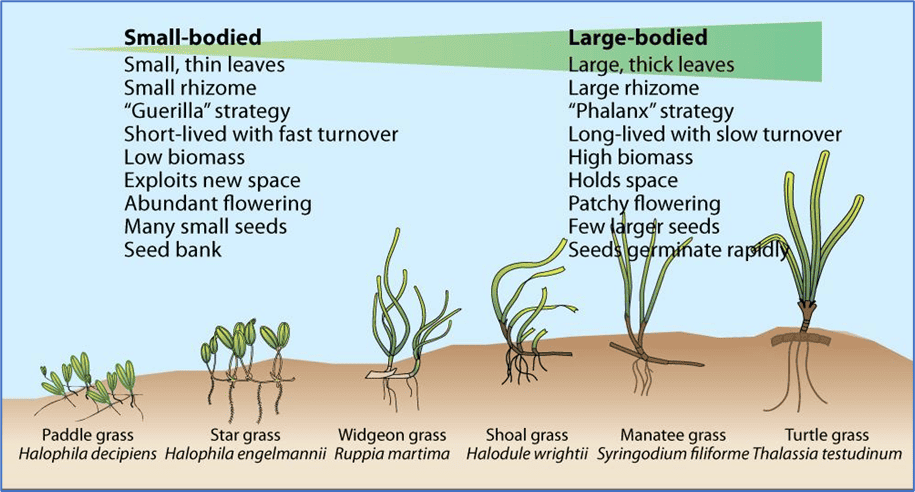

There are 49 species globally, representing 12 genera, with six of these genera found in the New World Tropics.

- Thalassia testudinum Banks ex König – Turtle grass

- Halophila baillonis Ascherson

- H. decipiens Ostenfeld

- H. engelmannii Ascherson

- Halodule wrightii Ascherson

- Filiforme Kutzing- Manatee grass

From “Tropical Connections: South Florida’s marine environment” (pg. 260), courtesy of the Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu), University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Seagrass beds are abundant in the Caribbean. Six species belonging to 4 genera are found in this region. In the Caribbean the dominant species is Thalassia testudinum, which can be found from Venezuela to Florida and is also known as Turtle Grass. If you guessed that this is named because marine turtles love to eat this grass, then you would be correct! Seagrasses can be found in both Trinidad and Tobago and are often closely associated with other oceanic ecosystems such as coral reefs.

Photo by: James St John.

Adaptations

They show unique adaptations to life underwater which include the ability to live in a saline environment. The optimum salinities for seagrasses are between 28-48 ppt with best growth under 35ppt though Thalassia can live in salinities approaching 60ppt. Other adaptations include the ability to sustain life and reproduce whilst fully submerged in water and a well-developed anchoring system. As much as 60% of the total biomass may be found in the below-ground tissues! These roots also stabilize the plants in the soft seabed and prevent the ocean currents from dislodging them, though currents between 1-2 knots are best for growth with stronger energies, such as during intense storms, uprooting plants. The plants produce fleshy to fibrous root systems and thick horizontal rhizomes which branch and produce short shoots and blade clusters above ground. The plants produce flowers which are pollinated allowing for sexual reproduction.

Photo by: James St. John for Wiki Commons.

Investments in this root system confers many advantages to the seagrasses but must be balanced with investments in photosynthesis-capable leaves as well. The leaves are relatively thin and flattened which allows the plants to exchange gases and nutrients between themselves and the water. The leaves are one example of convergent evolution, in which the various species of seagrasses have evolved to show similar morphologies based on adapting to their respective environments. Seagrasses are found in shallow waters (usually 0.5 to 5m in depth) as the leaves need sunlight to allow for photosynthesis, which peaks in waters at 28 to 30 degrees Celsius.

Oxygen can travel from the leaves to the roots, which allow for oxygen availability in the generally anoxic soils. Due to the high rate of metabolism in the microorganisms inhabiting the seabed, there is generally little oxygen found in the sediment, as well as a buildup of phytotoxins. Similar to the leaves, roots also uptake minerals and roots also allow for conversion of ammonia to nitrate. New studies show that the roots may have a symbiotic relationship to nitrogen fixing bacteria found both inside and surrounding the root systems, a process similar to terrestrial legumes, allowing for increased nitrogen availability.

Roles in ecosystem

Seagrasses often form complex ecosystems with other biota, including algae, corals, fish and invertebrates. The blades of grass offer substrate for epiphytic algae and single celled alga called diatoms, creating microcosms of life on each leaf. However, excessive covering of the blades by algae can lead to lower productivity as the algae reduce the amount of light available for photosynthesis and can also cause mechanical damage to the leaves.

Photo by: Ria Tan, Wild Singapore

One notable role of seagrasses is soil stabilization, which is important during storms and hurricanes and helps buffer the impact of these events on the nearby coastlines. The seagrasses also contribute to sediment retention and enrichment as the blades dissipate wave energy, trapping the sediment within the extensive mats of roots and rhizomes. The detritus created supports its own food chain, populated by organisms feeding on decaying plants and herbivore waste products. Some of these detritivores include bivalves, gastropods and mullet fish. Seagrass sedimentation can also play a role in helping to preserve human history! Some seagrass meadows have been discovered to allow for protection of shipwrecks and underwear heritage items as thick sediment builds up layers over artifacts, sealing them and slowing organic decay.

Photo by Paula Jones for Getty Images Signature

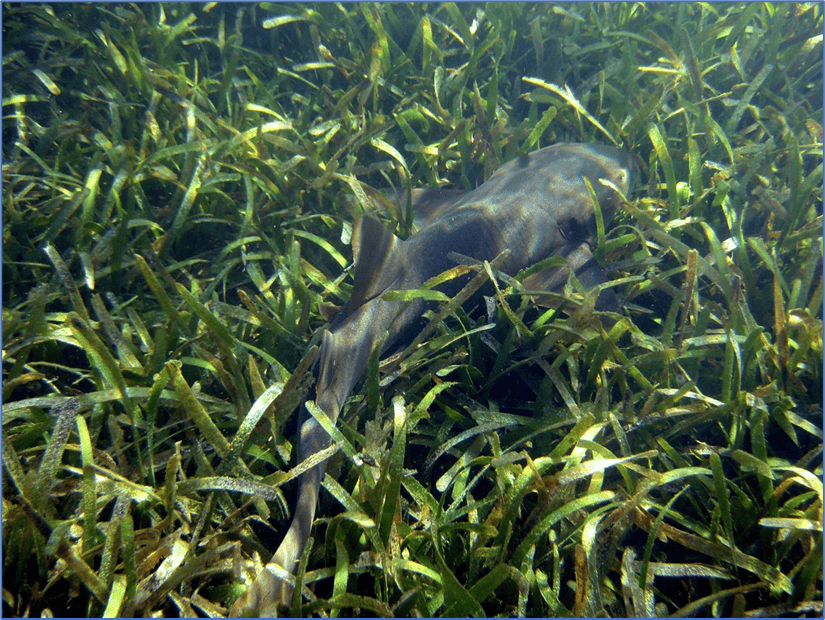

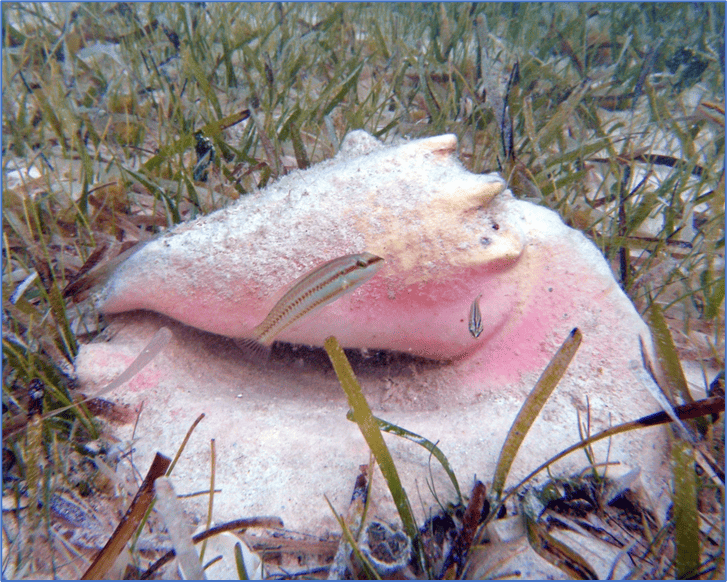

On a larger scale, the seagrass meadows can provide refuge for fauna such as fish and reptiles, including green and hawksbill turtles (Chelonia mydas and Eretomochelys imbricata respectively). Both juvenile and adults use the meadows both for shelter and for grazing, and these communities can support the tourism and fishing sectors. The blades may provide surface area for colonization by corals and sponges, as well as feed for animals such as sea urchins. These smaller animals attract larger predators such as carnivores, including fishes, crabs and shrimp. Fishes and larger vertebrates often migrate between meadows and other ecosystems such as coral reefs or mangroves. Some fishes that can be observed are parrotfish, groupers, barracuda and puffers. Southern stingrays may sometimes be observed feeding on mollusks. The meadows also act as a nursery for juvenile conch, lobster, shrimp, snappers and grunts, amongst others, and these species can be very valuable for the tourism and fisheries industries in the Caribbean.

Photo by Wayne for Flickr.

Photo by: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for Flickr.

Photo by James St John for Flickr.

Now that we know a bit more about seagrasses, stay tuned for upcoming articles where we dive into some more fascinating facts about these key species! Please note that much of information presented in this article was generously supplied by Dr. Rahanna Juman of the Institute of Marine Affairs and we thank her for her insights and contributions.