Despite the fact that wetlands are one of the most productive ecosystems on the planet with monetary values exceeding thousands of US dollars per hectare (De Groot et al. 2006), the majority (75%) of wetlands in Trinidad and Tobago, which is home to four mangroves species, are being suffocated by macro-plastic waste. According to Belix (2019), Trinidad and Tobago is considered a high plastic polluter (1.47 kg per capita per day) when compared to the regional average of 0.99 kg per capita per day, and the global average of 0.74 kg per capita per day (Kaza et al. 2018). During the period 2015-2018, the International Coastal Cleanup Trinidad & Tobago (ICCTT) reported that seven out of ten items collected were plastics (bags, bottles, caps, foam cups/plates, food wrappers, fork/knives/sporks, and foam take out containers), in addition to glass bottles, beverage cans and metal caps (Loop News 2018). These results should be treated with caution and may even be an underestimation as scientific designs were not applied to the study. Nevertheless, these findings are disturbing and should be used as baseline information.

Wetland ecosystems are part of a much larger ecological process responsible for preventing shoreline erosion, aiding floodwater retention, processing contaminates and poisons, ensuring watershed stability and purification as well as providing food and amenities to the citizens of Trinidad and Tobago (Alongi 2002). Moreover, mangrove plants can store 3 to 5 times more carbon than terrestrial forests, mostly in soil, and are essential to mitigating the negative impacts of global climate warming.

At present, Banks Village Environmental Organisation (BVEO), a recent non-profit organization, is rehabilitating 10 ha of wetlands north of the Caroni Swamp Protected Area, using a Community-Based Ecological Mangrove Restoration (CBEMR) multi-stage approach, and as expected, the Beetham community is actively involved in the project. About 500 lbs. or 227 kg of garbage have been removed to date in these ecosystems in northwest Trinidad. Some items collected include, but are not limited to: food tins, glass bottles, clothing, vehicle rims, tires, aluminum and steel galvanize, and numerous plastic products. More than 75% of the garbage collected were plastic products that were entangled in mangrove roots. In some cases, plastics products were found buried more than 1-feet deep in the soil, demonstrating the extent of pollution. The organisation also continues to work towards wetland conservation and public awareness, and aspires to create mainstream mangrove conservation clusters in Trinidad and Tobago.

Regrettably, the status of the Beetham Solid Waste Landfill could void our fight to conserve mangrove ecosystems in Trinidad and Tobago. The Caroni Swamp Protected Area, which is the country’s largest mangrove ecosystem, is situated south of the landfill area, and has been treating effluent from the landfill for many decades. Mangrove plants absorb excess nitrates and phosphates which are frequently released from human activities, thereby preventing contamination of nearshore waters. However, like any system, there is a carrying capacity, and the Beetham Landfill seems to have overwhelmed the swamp’s carrying capacity many years ago. At present, there is raw sewage and waste oil running out of settling ponds into the nearby wetland. Community members from the Beetham Estate Gardens have been observing the destruction of the mangrove trees for many years and are not only concerned about the ecology but the build-up of lethal underground gasses that could give rise to an explosion at any time. Therefore, the country needs to find innovative ways to treat these issues.

Based on preliminary surveys conducted by BVEO, many landlocked Trinbagonians believe in climate change. Furthermore, our citizens recognize wetlands have declined and flooding, as well as coastal erosion, have increased on the islands. However, very few landlocked citizens were able to link the negative impacts of climate change to human actions. When coastal Trinbagonians were asked the same questions, they not only recognize the rise in disasters but were also able to relate them to causative agents and recommended possible solutions. Clearly, because these citizens depend heavily on coastal resources, they are more knowledgeable and sensitive toward global climate change, as they are directly affected by negative changes in the environment.

For example, the villagers in the Otaheite community of south Trinidad are constantly under siege from seawater rise and wave action to the extent that homes on the coastline are often inundated with water; children occasionally have to walk through water on their way to and from school and fisherfolk are prevented from accessing their vessels to continue their trade, which is a key source of community livelihood.

The sea defense or barrier once provided by mangrove plants no longer exists and the villagers seem convinced that the dumping of wastewater from the nearby industrial soft drink manufacturer is to blame. This is not to say that they don’t also acknowledge that plastic pollution and the callus cutting down of the wetland tree species have also played a role in what has now resulted in the overall loss of wetland coverage in the area. Therefore, this has prompted the question of whether there is a need for greater monitoring and regulation to make both industrial and domestic offenders more accountable for indiscriminate dumping of waste and/or related proven destruction of the environment and our resources?

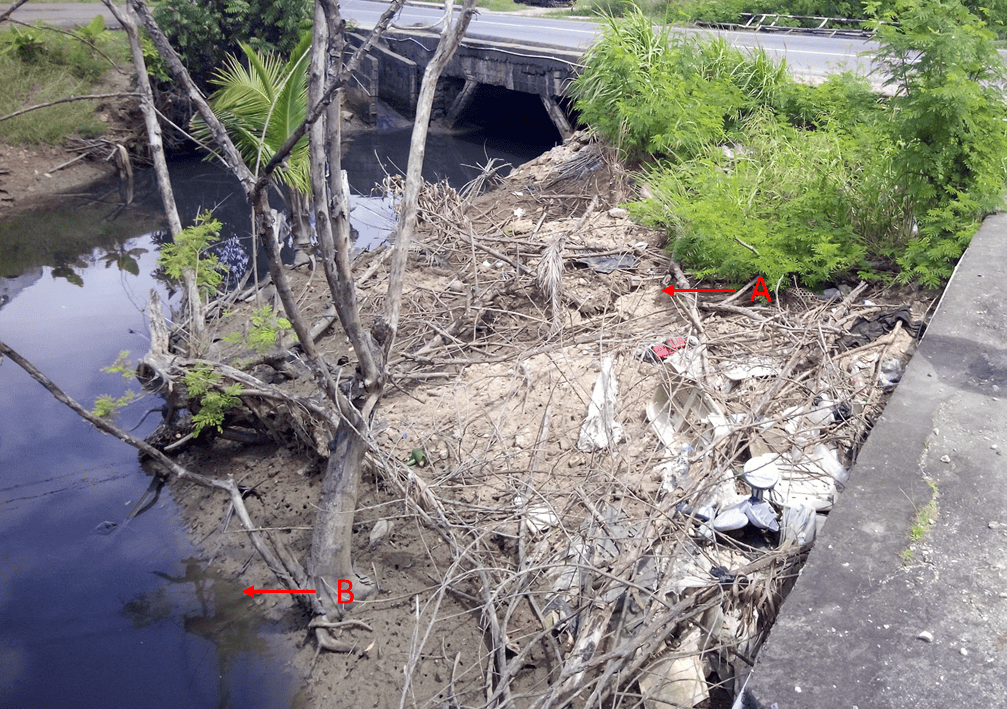

Note: vegetation die-back within the intertidal region (A-B) due to industrial effluent and plastic pollution.

With the ever-increasing single use of plastics in the food industry and the guaranteed increase of plastic waste, wetland ecosystems throughout the country will suffocate in plastic carpets, unless immediate actions are taken. Ideally, fighting the battle of global plastic contamination should be focused on long-term and sustainable approaches such as education and awareness, cultural transformation, and increasing taxes in cities with considerably high plastic waste output or an under-utilization of state-owned disposal services. These approaches can take decades to achieve, and it may already be too late to safeguard ecological services provided by wetlands. A simpler more practical way of dealing with this problem in the short-term is to remove existing plastic garbage from wetland ecosystems throughout the islands. This will allow them to breathe effectively and provide their numerous ecological services until long-terms mitigation approaches can be enforced.

Tackling the problem of reducing anthropogenic impacts on wetlands in Trinidad and Tobago is complex but not impossible, and requires on-going consultations throughout sectors and households all around the country. Clearly, this is a long-term undertaking that may require a significant outlay of funds. Nevertheless, if the government promotes proper sanitation techniques where the emphasis is placed on innovation and entrepreneurship alongside improvements in our education system, it would be beneficial. Additionally, we recognize that for a developing economy such as ours the capacity and capability to properly manage the present plastic usage is attainable through monetizing recycling, speeding up national legislation, promoting community incentives, and investing in technological innovations. But it is also expedient to avoid high plastic importations altogether.

This article was also made possible with contributions from Mrs. Sherry Smith-Pierre, the Project Manager of Banks Village Environmental Organization (BVEO).