Every year hundreds of millions of wild plants and animals are illegally removed from forests and traded for up to US $23 billion dollars. This harmful trade in wildlife often supports rural communities, but only temporarily.

In the long-run, illegal and unregulated wildlife trades contribute to the loss of ecosystem goods and services, as well as potentially sustainable industries such as ecotourism and recreational hunting.

In Trinidad and Tobago, we are already seeing substantial damage to our forests, but it is not too late. We can end the ‘dangerous experiment’ by adopting precautionary, science-based policies developed by and for our rural communities.

Trading Away the Forest’s Bounty

The forests of Trinidad and Tobago provide a wealth of ecosystem goods and services, from tangible products like timber and food to more intangible processes like flood control and micro-climate regulation. Yet our forest ecosystems are being unsustainably traded away, and this threatens the quality of life of everyone who depends upon them.

Roy Corbin of Corbin Local Wildlife in Tobago reflects, “We need forests to stay alive and we are losing our forests very fast right now. A lot of illegal logging is still taking place in the Moriah area, and many other parts of the island. You can hear the sound of chainsaws at night.”

Beyond illegal logging, many species of forest animals are being displaced. This includes monkeys and birds that play important roles, like the dispersion of seeds.

“Each animal has its important role in the forest, so when we remove them we are doing harm to the forest. The manicou (Didelphis marsupialis) is disappearing so fast, and its role is to clean up carrion and pests. If they ban unsustainable hunting, the animals will restore balance to the forest.”

The Missing Songs of the Forest

The wildlife trade has taken a noticeable toll on local songbird species in Trinidad Tobago.

Faraaz Abdool, a wildlife photographer and member of the Trinidad and Tobago Birds Status and Distribution Committee, can identify at least nine species of songbirds that have now vanished from the local wilderness, including large seadeaters like the Large-billed Seed-Finch ‘Twa Twa’ (Oryzoborus crassirostris) and Grey Seedeater ‘Picoplat’ (Sporophila intermedia).

“Local ornithological records show that when the larger seedeaters began disappearing, trappers turned to the smaller and then abundant Ruddy-breasted Seedeater ‘Robin’ (Sporophila minuta) and exterminated that population within a generation,” says Abdool.

Another popular songbird that is still a common sight is the Chestnut-bellied Seed-Finch ‘Bullfinch’ (Sporophila angolensisis). However, it is commonly seen caged.

Nearly all Bullfinches in Trinidad and Tobago are imported in bulk from Venezuela in high mortality conditions. Controversy also surrounds this bird as some folks blame the decline of the bullfinch on pesticides used around this habitat. Yet, Abdool observes that other birds that share the same habitat are still abundant.

“It is worth noting that of the species which managed to survive, none have melodious songs,” Abdool adds.

Introducing Non-Natives and Invasives

Unsustainable extraction isn’t the only problem caused by the harmful wildlife trade. The pet trade introduces alien species that compete with natives and upset local ecosystems.

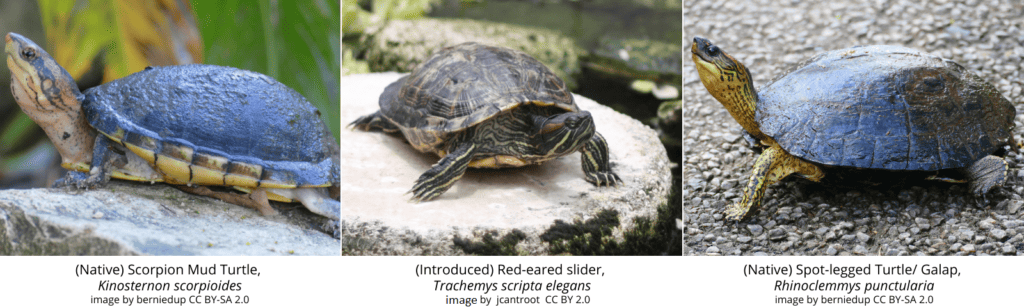

One widely introduced species in Trinidad is the Red-eared Slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans), which is commonly sold in pet shops.

Dr. Ryan S. Mohammed, aquatic biologist and advisor to the Nurture Nature Campaign explains, “If you look at the red eared slider distribution for Trinidad it resembles a distribution map of anthropogenic impacts, a settlement or an artificial dam. It means that their spread is directly linked to human intervention.”

This invasive introduction of Red-eared Sliders into Trinidad is particularly concerning for Mohammad.

“They’re bad for the environment because they are more aggressive than our native species. Apart from that, they have a very wide diet. I have never seen them refuse anything, whether it be plant or animal. And in captivity, I’ve seen Red-eared Sliders decapitate native juvenile Galap and Scorpion Mud turtles.”

Another species of concern is the Tufted Capuchin (Cebus apella), an introduced primate that has established a population in Chaguaramas.

Wildlife ecologist Darshan Narang explains that “introduced animals become ‘invasive’ when they cause harm to the natural environment, human health, or to our economy.” Unfortunately, this is potentially the case for Tufted capuchins that are trafficked into Trinidad from South America.

“Tufted capuchins are generalists, adapting to any habitat and eating almost anything from insects, fruits, leaves, flowers, bird eggs to even frogs. They can survive anywhere. If they reach the sensitive forests of Nariva Swamp and the Trinity Hills, they may have a negative effect on our two native primates, the Red Howler and the Trinidad White-fronted Capuchin.”

Community-Supported Wildlife Management

Scientists and other experts believe it is still possible to heal our damaged ecosystems. The key first steps are baseline research, science-based legislation, and—most of all—community collaboration.

One rare example of success is the Pawi (Pipile pipile), an endemic and illusive bird found in the forests of north-east Trinidad.

According to Dr. Mark Hulme, zoology lecturer at the University of the West Indies, pawi populations declined from the 19th to 21st century, likely due to overhunting, until there were only 300 pawi left in the wild. This resulted in the species being classified as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Nevertheless, Hulme highlights how legislative changes and community-based conservation may have allowed the species to continue in the wild.

“The designation of the Pawi as an Environmentally Sensitive Species, the publication of the Pawi Species Recovery Plan and the educational “Pride in the Pawi” project led to greater awareness of the special place the Pawi has in Trinidad’s natural heritage. This appears, anecdotally, to have reduced hunting pressure. Pawi are starting to be seen in areas where they have not been recorded for several years.”

Hulme hopes to advance science-based policy by updating the distribution data and population estimates of Pawi, using audio recorders to detect their distinctive wing drums.

Science-based assessment is a key component to monitoring and managing the recovery of overexploited species and forests, and has already driven success locally with the reintroduction into Nariva Swamp of the blue and gold macaw (Ara ararauna).

We all hope there are many other success stories to come.