Many in Trinidad and Tobago are already familiar with the leatherback turtle that visits our shores yearly from March to August. What is less familiar to most locals are the four other hard-shelled sea turtle species that can also be found here: Hawksbill, Green, Loggerhead and Olive Ridley.

These five species share some common characteristics. They all spend the majority of their long lives at sea, travelling great distances, with females returning to beaches near their birthplace to lay large numbers of eggs.

In celebration of World Turtle Day, observed annually on May 23, I’ll be detailing some fun facts about T&T sea turtle species in this article on behalf of my team at SpeSeas. We hope that you discover what makes each species unique and become an active participant in helping our sea turtles to survive and thrive.

1. Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) – Vulnerable (IUCN)

Leatherbacks are the largest sea turtle and spend a significant portion of their lives in the vast open ocean, travelling distances that span thousands of kilometres. They can be found in all tropical and subtropical oceans with a range that extends into the much cooler Arctic circle.

What sets leatherbacks apart from other sea turtles is their soft, leathery shell, which enables them to dive deeper than any other species of sea turtle. Their main diet consists of soft-bodied animals that drift throughout the water column such as jellyfish.

For nesting season, they favour warmer climates like ours here in T&T. Our land is home to one of the largest populations of nesting leatherbacks in the world, and as such, has played an important role in global conservation efforts.

While global populations are considered to be vulnerable, our regional subpopulation is currently classified as endangered (a more alarming designation) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) due to recent declines.

The primary threat to Leatherbacks, globally and locally, is considered to be bycatch in fisheries.

Unlike the leatherback, the other four sea turtles found in T&T are hard-shelled

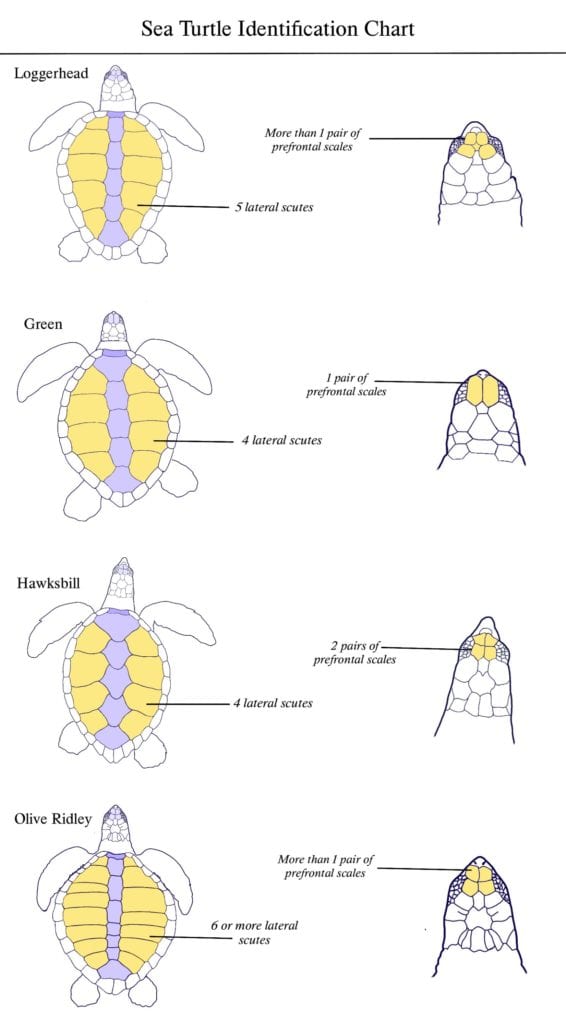

All hard-shelled sea turtles have bony plates called scutes that make up their shell, and the pattern of these – in addition to the number of prefrontal scales between the eyes – is key to confirming the species of an individual.

2. Hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) – Critically Endangered (IUCN)

After leatherbacks, hawksbills are the next most common species that nest on our shores. They are small, agile turtles and their nesting activity is scattered over many beaches throughout our coastlines, including small bays protected by rocks or reefs. Mature females make breeding migrations between foraging and nesting grounds on the scale of hundreds to thousands of kilometres.

Juveniles of this species are also found in our waters year round –in coral reefs, underwater cliff walls and hard bottom habitats– where they feed primarily on sponge. Through this unique diet, they help maintain the diversity and health of our coral reefs. If you snorkel or scuba dive, this is the species you will encounter most frequently.

Hawksbills can be recognized by their four lateral scutes, two pairs of prefrontal scales, and their narrow, pointed beak. The scutes on their shell overlap like shingles on a roof, resulting in the serrated appearance of the shell, which is more prominent in juveniles.

Hawksbills are distributed throughout the tropics and to a lesser extent the subtropics. Turtles born on our shores will migrate widely across the Caribbean region, with females returning to nest.

The juveniles found in our waters are distinct from our nesting population, and originate from a variety of other nesting beaches across the region, including as far away as Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Sadly, Hawksbills have been harvested for their beautiful “tortoiseshell” which in the past was used to make jewellery and other decorative items. IUCN lists them as critically endangered.

3. Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) – Endangered (IUCN)

Green turtles are the largest of the hard-shelled turtles and are uncommon on our nesting beaches. Just like the hawksbill, however, juvenile greens can be found living offshore year-round. This species is herbivorous and feeds on seagrass and algae. They may be found in seagrass beds but also in coral reefs and other habitats where algae may be present.

I have often observed greens around rocky coastlines of the north and east coasts of Trinidad.

The grazing activity of these turtles plays an important role in maintaining the health of seagrass beds and coral reefs. They can be distinguished from hawksbill turtles by their blunt beak and they are the only species with only one pair of prefrontal scales between their eyes.

While the meat from the Green turtle has generally been the most sought after among all the species worldwide, both hawksbills and greens continue to be threatened locally by poaching for meat on our beaches and at sea. IUCN lists them as endangered.

4. Loggerhead (Caretta caretta) – Vulnerable (IUCN)

Loggerheads are considered rare in T&T but a number of sightings have been confirmed over the last 12 years including off the east coast, south coast and Chaguaramas in Trinidad – as well as around Tobago.

One Loggerhead stranded on the east coast of Trinidad in 2017 and was subsequently released with a satellite tag after successful rehabilitation. Satellite tracks showed that this loggerhead spent some time exploring the Gulf of Paria after being released.

Loggerheads are distinguished from other species by their large heads and the five lateral scutes on their shell. Hatchlings may easily be mistaken for hawksbills if you don’t pay attention to the pattern of scutes on the shell.

Loggerheads can be found in muddy and hard bottom habitats where they feed on a variety of animals including shellfish that they crush with their large heads and strong jaws.

Loggerheads nest along shorelines in tropical and temperate zones, and can be found in all tropical and temperate ocean basins. The largest nesting population of Loggerheads in the world is in Florida. IUCN lists them as vulnerable.

5. Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) – Vulnerable (IUCN)

Olive Ridleys are also considered rare in T&T, but there have been a number of recorded sightings on our beaches and at sea. Olive Ridleys have a varied diet (that can include crabs, snails, barnacles, algae, fish, jellyfish and other soft-bodied animals) and are known to feed in soft bottom coastal habitats and at the surface in the open sea.

They are the smallest of the sea turtles found in T&T, and usually have six or more lateral scutes, making them distinct from the other species we encounter locally.

In some places around the world, Olive Ridleys exhibit a unique nesting behaviour called an arribada, where many thousands of nesting females coordinate and nest on a single stretch of beach over a period of a few days. During the nesting season these thousands of females remain close to their nesting beach for several months. However this behaviour is not observed locally; we only see the occasional solitary nesting turtle.

IUCN lists Olive Ridley as vulnerable.

Sea Turtles – Value and Threats

Sea turtles are ancient species that were once abundant around the world, and play important roles in maintaining healthy marine ecosystems. They have been harvested for thousands of years for meat, eggs, shells and other products, including intensive harvest in the Caribbean by European colonisers in the 17th and 18th centuries, which significantly depleted the populations to a mere fraction of what they once were.

Around the world, and right here in T&T, sea turtles have been shown to generate significant revenue from eco-tourism activities including tours to nesting beaches and activities like SCUBA diving.

Sea turtles continue to face numerous pressures including continued harvest, bycatch in fisheries, habitat loss, climate change and plastic pollution. All five sea turtle species found in T&T are considered globally threatened, and have been designated as Environmentally Sensitive Species. The penalty for harming these species is $100,000 and imprisonment for two years.

We are still learning about sea turtles around Trinidad and Tobago and you can help contribute to research efforts. Become a citizen scientist and help us learn more by reporting your turtle encounters to us! Find out more about this project here: https://speseas.org/projects/sea-turtle-citizen-science/