A wedge-capped capuchin monkey, showed up on death’s door last month at the Las Cuevas home of Cari-Bois News, citizen journalist, Arlene Williams. This encounter triggered a series of interventions that would eventually lead to a bittersweet conclusion for the injured animal. Recounting her experience, Williams shares this report with Cari-Bois News.

November 23: I was doing laundry on what seemed to be a perfectly ordinary morning, when I heard my mother’s voice yell out, “look a monkey!”. At first, I thought she was making fun of one of my nieces until she remarked, “look how close it is!”.

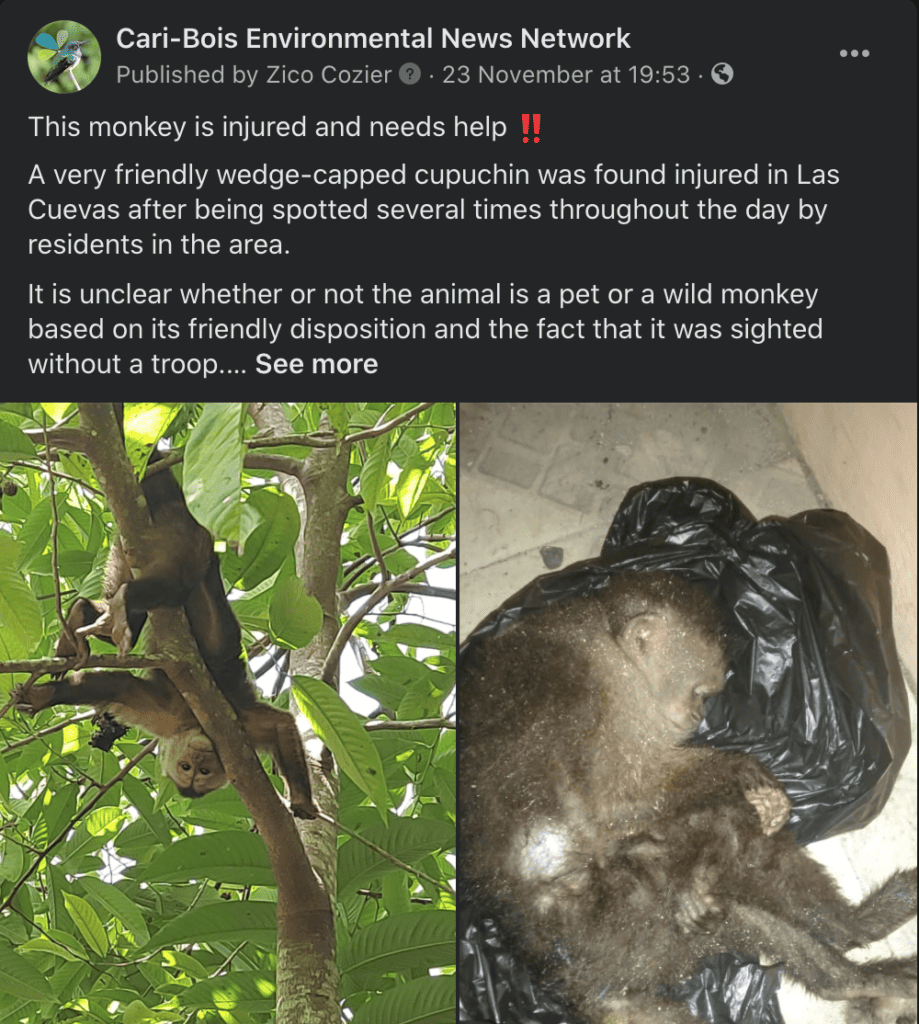

My curiousity piqued, I decided to go check it out for myself. To my surprise, I saw a small but seemingly tame monkey shuffling through our pomerac tree before swinging across to the neighbouring sugar apple tree. I had never seen a monkey like this before in our busy little community of Las Cuevas, so I excitedly rushed for my phone to capture some photographs of our playful visitor. The monkey seemed to be very comfortable in our presence and appeared to be wearing a red collar around its neck. After approaching, closer and closer, and cutely nicking a snack from my kitchen, the monkey continued on its way and I assumed it must have been headed back home to its owner.

Later that same evening a friend of mine sought me out to say he had also spotted a monkey in our community. His description of the animal however, made my heart sink.

“I now see a monkey at de side ah de road dey – like it get shock and dead,” he said.

Being the president of the Las Cuevas Eco Friendly Association, an NGO committed to the conservation of leatherback sea turtles nesting in Las Cuevas, I knew this was just another type of animal that needed my help. I knew I had to do something.

I asked my friend where he saw the monkey. “Right up Hotel Road,” he replied.

I stopped what I was doing and immediately ran towards the monkey only to find it passed out, at the side of the road, bleeding from its nose.

I carefully moved the monkey to somewhere safe and began contacting citizen journalists and environmental activists within the Cari-Bois News network for advice on the best course of action. In the meanwhile, Cari-Bois News put out a call for help, seeking assistance to get the monkey a late-night veterinary appointment to see if anything could be done to save its life.

An animal enthusiast with experience volunteering at a wildlife rehabilitation centre, responded to the call volunteering to drive to meet me in Las Cuevas, collect the monkey, and carry it to a friend of his who is a vet.

The prognosis was not good. The monkey seemed to be struggling to breathe and the vet suspected it may have been suffering as a result of poor diet or poisoning. Its teeth were filed and its skin was drawn to the bone. The vet speculated that whoever owned the monkey either mistreated it or did not have the necessary knowledge to care for it. The vet told us the monkey would need to be checked in to a well-equipped veterinary facility where it could be placed on an IV drip. The intervention could cost upwards of $10,000 TTD and there would still be no guarantee that the animal would survive.

At this point, I reached out to Ricardo Meade, founder of the El Socorro Centre for Wildlife Conservation who identified the species as a wedge-capped Capuchin. However, he dealt another heartbreaking blow to its hopes of finding a happy ending.

“The best thing to do is to put it down because there’s too many in our country and they deliberately terrorise, hurt and sometimes kill the white fronted capuchin which actually lives here in T&T,” he said.

As sad as it was, I fully understood Meade’s perspective. He explained that El Socorro Centre for Wildlife Conservation was already caring for other monkeys of this breed and that because of the growing illegal wildlife trade in Trinidad and Tobago, centres like his are running out of space and resources to care for abandoned exotic pets that can never reenter the wild.

Meade recently sounded the alarm nationally on how invasive species like this wedge-capped capuchin were being smuggled into Trinidad and Tobago from Latin America and sold illegally to owners with little understanding of the animal’s needs.

Faced with the facts and wanting to at least give the animal a fighting chance, I decided to hand over the monkey to the Emperor Valley Zoo, where they would be able to try to save it.

On receiving the animal, they warned that the monkey – which they identified as female – was facing a less than 50% chance of survival. I waited for one week with baited breath to find out if the monkey would make it.

Finally, the call came and I learnt that the monkey’s condition had stabilised. At first I was jumping for joy but the news was bittersweet – on one hand I was happy that the monkey would live but on the other hand I felt sad that it would never get to reenter the wild and experience life the way a monkey should.

I thought that this would be how this story ends but then one day I received an unexpected phone call out of the blue – it was the owner and they wanted their monkey back. I asked, “did you know that this is an invasive species?”, to which they replied, “yes I do.”

When I sent them a photograph of the monkey’s condition, they told me they hoped it would survive.

“The monkey used to stay inside the house in the day but at night it sleeps in a cage,” said the former owner who only agreed to speak on condition of anonymity for this story.

They said She said the day the monkey got away, it was tied to a string and it unhooked itself. I informed the owner that the monkey had been handed over to the zoo and there was nothing more that I could do.

I share this story because I want it to serve as a cautionary tale. All wildlife is best appreciated in its natural habitat. A small gesture such as getting an exotic pet, could have devastating consequences, throwing off entire ecosystems, if the animal escapes into the wild. Some may agree with the course of action I chose to hand it to the zoo while others may side with Meade’s perspective – but the truth is, we would not have to be having this debate about the ethical course of action for rescuers if the illegal wildlife trade could be dismantled. This for me has been a learning experience and has lit up a new fire in me to pursue the work I do in conservation. As for the monkey, I look forward to visiting her one day at the zoo where I hope she will have the best life she possibly can after a difficult early start.

Conservation officers at Forestry Division in the Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Fisheries were consulted and advised on every step taken as this story developed.